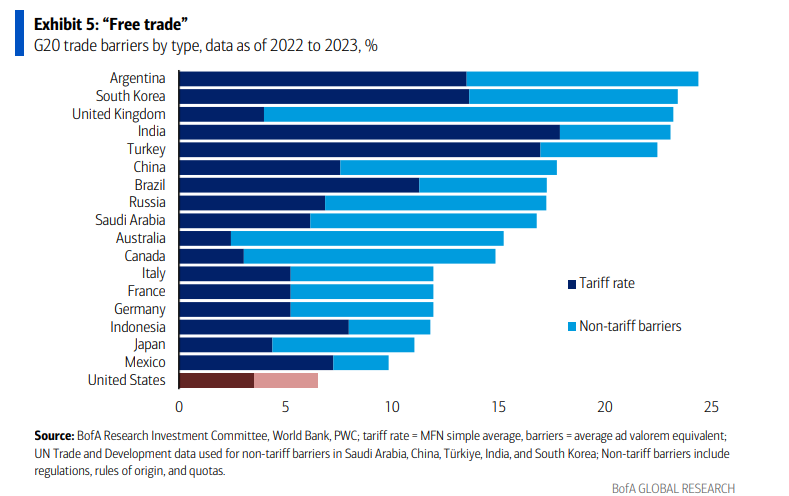

What a week. Let me begin by saying that until Wednesday, the US generally had lower tariff rates than its major trading partners. That is a fact, and a case can be made for why reciprocal tariffs in pursuit of fair trade is in America’s best interest. This fairness — or reciprocity in trade — would entail either America’s raising its own trade barriers1 without its trade partners responding in kind, or America’s trading partners lowering theirs in order to close the gap.

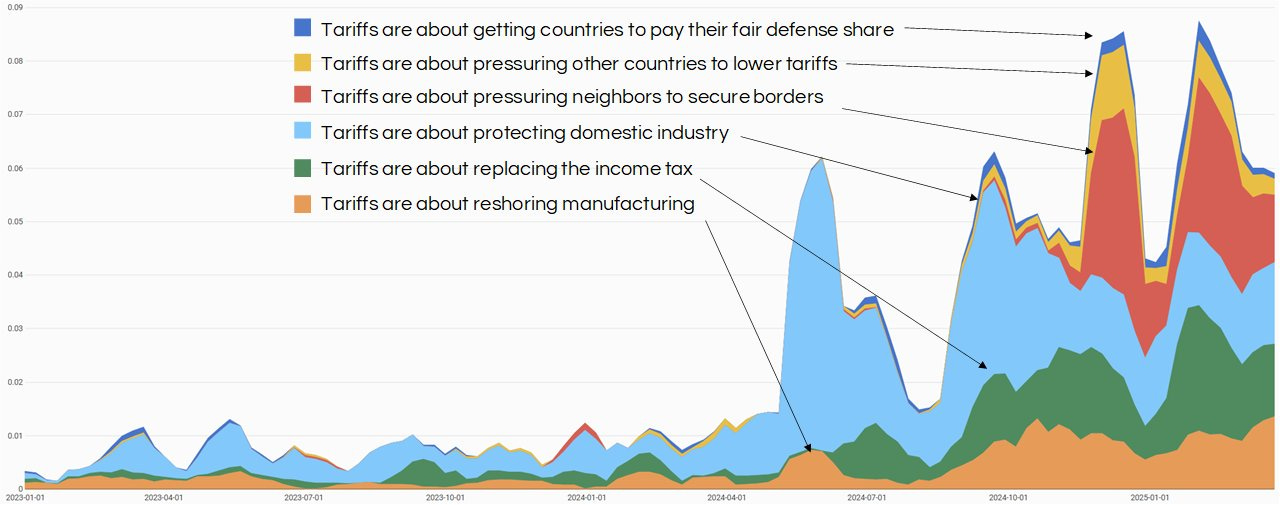

The narratives surrounding Trump’s longstanding tariff bent have centered around protecting domestic industry and reshoring manufacturing. But since the election, ancillary narratives have been shopped around by the administration (none of which have stuck), ostensibly in a sort of ‘kitchen sink’ approach to justifying the seemingly inevitable tariff hikes:

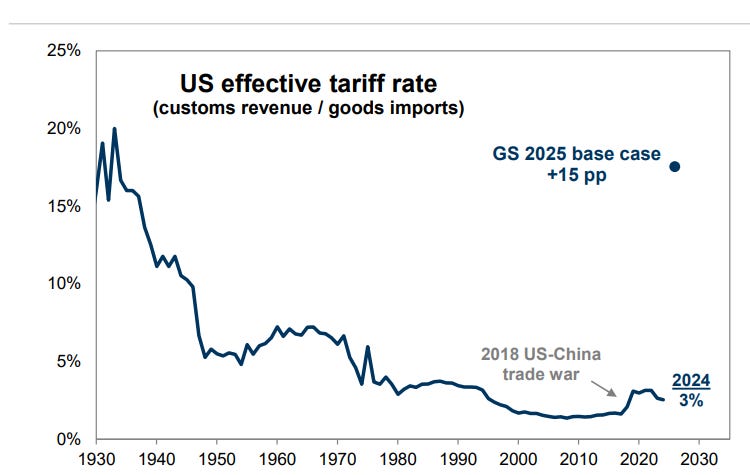

Going into Wednesday’s announcement from the Rose Garden, expectations were broadly for the US to raise its effective tariff rate by some 15 percentage points:

The ideal outcome would have been Trump’s announcing a plan for thoughtfully constructed, gradually phased-in tariffs targeting some combination of industrial reshoring and incremental revenue generation for the federal government. This would, ideally, be coupled by indications of intent to ultimately bring down barriers with America’s largest trading partners through negotiation. And in a perfect world, the tariffs would be accompanied by a coherent plan for initiating deregulatory efforts designed to offset the growth overhang caused by them. None of this happened.

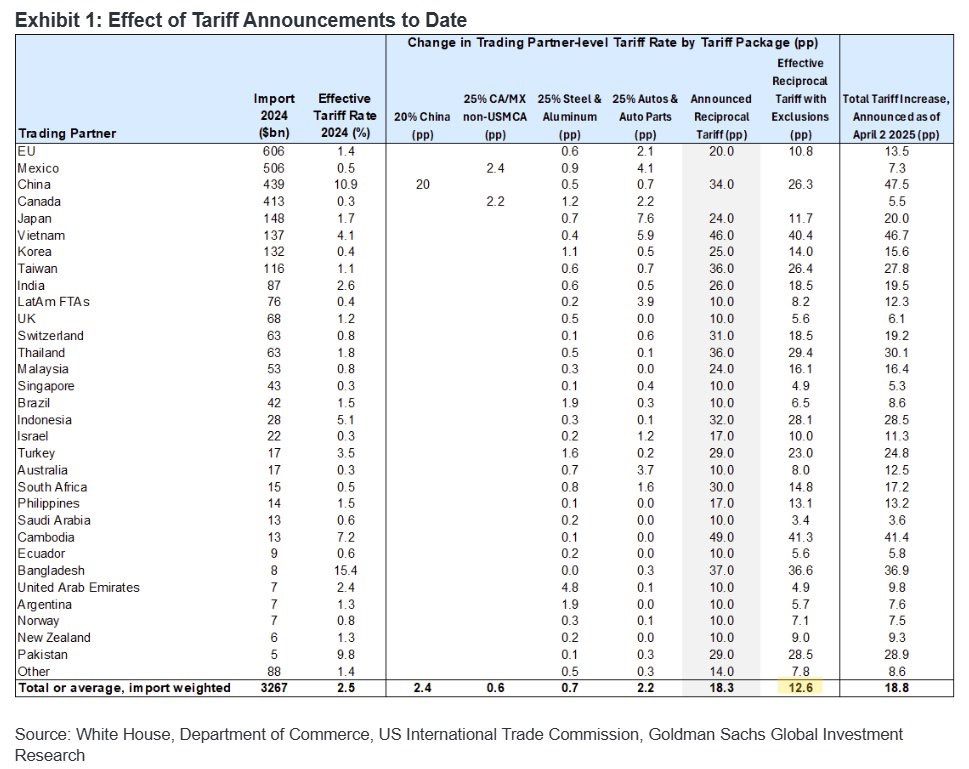

Instead, the outcome was not targeted reciprocity but a blanket application of tariffs based on trade deficits, amounting to an overall import-weighted average tariff rate of 18.3% (around 3% higher than what Goldman and many on Wall Street had expected). However, roughly one third of total imports were made exempt on account of intermediate goods — or inputs — like steel, copper, gold, and lumber; this should, fortunately, mute the inflationary pressures to some extent.

These exceptions, according to Goldman’s analysis, rendered the increase in the effective tariff rate only 12.6% — well short of expectations for a 15% increase:

Notwithstanding the misleading headlines reading “Trump raises tariffs to 25%!”, the tariffs announced were nominally in-line with or even below Street expectations. But given the sharp reaction in markets on the heels of ‘Liberation Day’, it begs questioning the degree to which the “take him seriously, not literally” line of thinking had persisted.

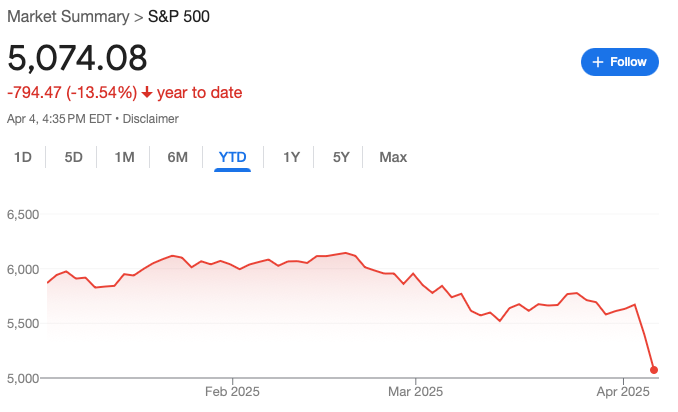

Indeed, the S&P suffered its worst weekly loss (9.1%) since March 2020:

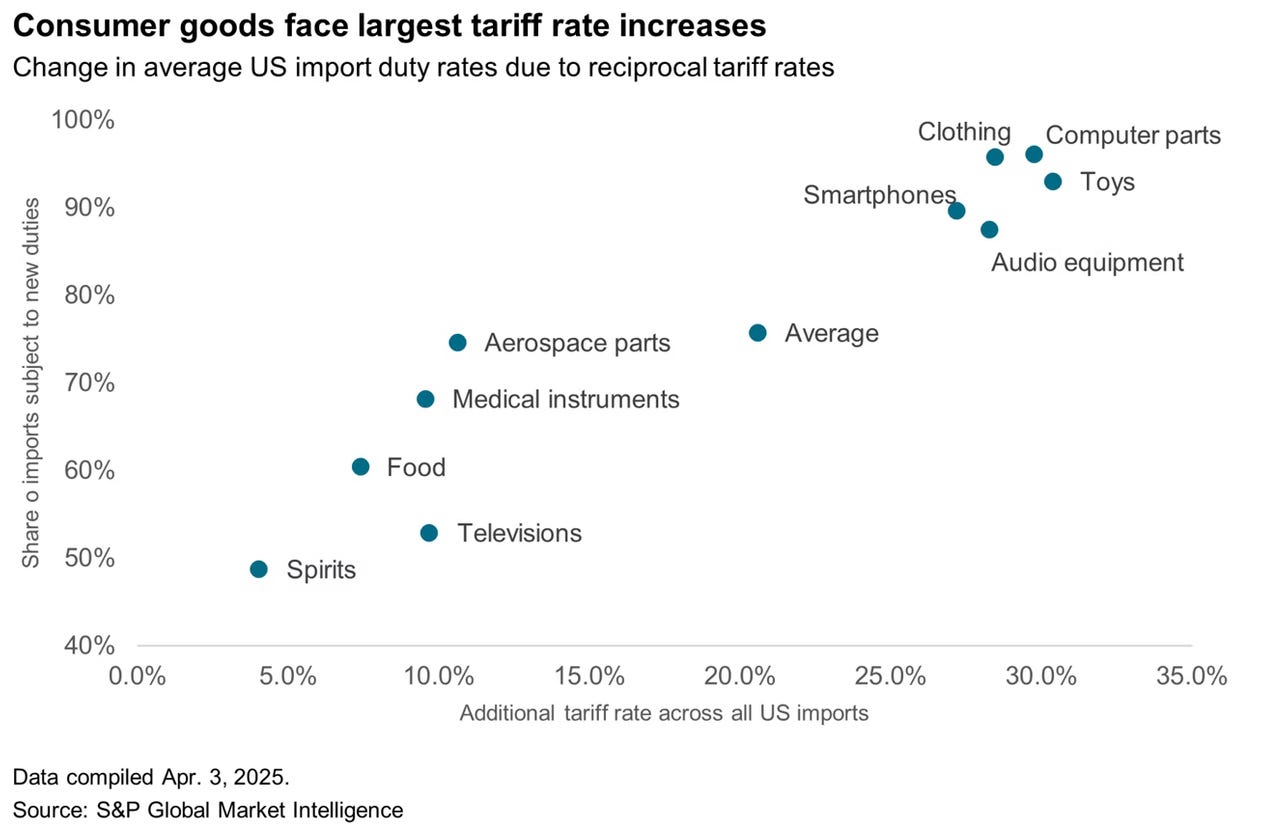

Now, the — or, one of the — problems with the way the Trump administration decided to proceed with tariffs is that if the goal is in part to bring manufacturing and jobs back to the US, well, that’s simply never going to happen for certain goods and industries. Take textiles and apparel as examples, both largely manufactured and exported to the US from countries like Indonesia or Vietnam, for whom an overwhelming portion of total exports are these finished goods.

First, the US labor force doesn’t have the skills necessary to work in textile manufacturing. Second, the difference in what it would cost under US labor laws and what it currently costs, let’s say, Nike to manufacture a sneaker in Vietnam is far greater than the incremental cost burden imposed by Trump’s new tariffs. In fact, in other words, Trump would probably have to raise the tariff rate on goods imported from Vietnam hundreds of percentage points for it to make financial sense for Nike to manufacture them in the US.

This is also likely true for a modicum of other consumer goods that the US largely imports, some of which are now, too, subject to large “reciprocal” tariffs:

In the meantime, Nike and others must eat these new costs or pass them on, which is why “the impact of the levies on Vietnam alone would require price increases of 10% to 12%” for retailers, according to UBS analysts.

Despite Trump’s assurances that these new tariff measures will stand as is, that rhetoric is unlikely to be true for two key reasons:

Retaliatory measures like the ones China announced on Friday are likely to ensue, which could unleash a tit-for-tat escalation into further increases in tariffs from both sides.

Certain US trade partners will come to the negotiating table in hopes of reaching bilateral trade agreements with lower overall trade barriers than before. We have seen this unfold with several countries, notably Vietnam on Friday.

And come on, we know how Trump is — he can’t resist the opportunity to be seen as negotiating on behalf of the American people. The Art of the Deal!

*Sigh*

So, depending on how things play out, the overall impact of Trump’s tariff regime hangs in the balance. I think this is one of the reasons why markets reacted so poorly: ‘Liberation Day’ was expected to — and very well could have — add clarity to the administration’s trade policy. Instead it gave rise to even more uncertainty.

If you’re Nike or some other US-domiciled global company who recently migrated its supply chain out of China and into one of the more US-friendly neighboring countries, you have a glimmer of hope that tariffs might spare you, but the crude deficit-based formula leaves you and your investors guessing as to whether the business will face higher costs or another burdensome reshuffle of suppliers, or both.

The long and the short of it is that taken on the whole, yes, Trump’s tariff increases do reflect a realignment toward reciprocity of trade barriers imposed by America’s trading partners — a return to fair-er trade, if you will (however haphazardly so). To what extent the administration’s push to use tariffs in the interest of balancing the trade deficit is a worthwhile one, however, remains highly debatable.

On the one hand, the US has some legitimate grievances. If we go back to the 1990s in the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse, the US had a sort of unipolar moment where China was still very much an underdeveloped economy and since the US stood to benefit from the cost savings of cheap labor in the form of lower consumer prices, tariff-free trade made a lot of sense. This was supposed to be a force for market reform and maybe even democratic reform in China. But that’s not how things played out. As China’s economy rapidly developed and as it grew to rival the US economically and geopolitically, it didn’t become more market-based. Instead, it closed its capital account and implemented a myriad of other anti-US trade barriers — many of which have led to a widening trade surplus with the US.

On the other hand, trade deficits aren’t necessarily bad. America’s (or any nation’s) current account is equidistant from zero as is its capital account, like two sides of a ledger. That is, the current account deficit, driven by higher imports than exports, is neatly offset by a capital account surplus, where foreign investors demand US assets like bonds, balancing the nation’s payments. This interplay showcases the balance of payments identity: a trade shortfall is funded by capital inflows, reinforcing the dollar’s dominance as the world’s reserve currency. A capital surplus means global trust in the US economy, and it also allows the Treasury to continue auctioning off bonds decade after decade despite racking up dozens of trillions in debt from money pit wars and the rest. It’s a tight, powerful cycle that fuels America’s economic clout… for now.2

If raising tariffs is a foregone conclusion for the US (Tariff Man decree), instead of a spray and pray approach, we should be wielding the tariff gun in a targeted and measured manner. The gripe is with China (and there’s a reason why the Biden administration didn’t rescind the Trump 1.0 tariffs, which almost exclusively targeted China); the gripe is not with Vietnam or Indonesia, as levying tariffs on these exporters hurts US firms and consumers as much as it hurts them.

In short, the best outcome from here and one that is feasible would be to quickly cut "deals" with friendly Asian countries — Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam, Indonesia, etc. A modest 10% tariff paired with true “reciprocal” tariffs (designed to be negotiated down to zero) would be reasonable, given that tariffs are evidently a necessity according to Tariff Man, whom voters understandably elected to liberate the country from an encroaching blob of bureaucracy and globalization, both of which have been far too unkind to far too many Americans — in the Rust Belt and elsewhere.

“Trade barriers” includes tariffs, along with regulations, rules of origin, and quotas.

See: the many criticisms of Modern Monetary Theory.

"In short, the best outcome from here and one that is feasible would be to quickly cut "deals" with friendly Asian countries — Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam, Indonesia, etc."

This seems like the most likely outcome. The irony is that Trump's strategy is basically reconstructing TPP, the free trade agreement Obama negotiated with allies that was never ratified since free trade agreements became politically untouchable after 2016. Trump's approach though is much more politically acceptable to the American public.

If this is what actually happens, Trump deserves credit for more astute political instincts compared to Obama.

Trump blew it! Tariff rates based on deficit ratios is senseless. Your best visual is the shifting narrative plot over time. When you can’t explain why the policy is developed in the first place, then you can’t count on a stable basis to keep the policy around. Business confidence suffers and investment stagnates. His approval rating is bound to keep sinking if this keeps up.

I would like thoughtful fair trade with targeted tariff applications. Oh, well!