WEEKLY POLL

→ Last week’s poll

Will China (militarily) make a move on Taiwan by the end of 2026?

63% - No ✅

37% - Yes

→ This week’s poll

PREDICTION MARKETS

→ (Dis)inflation?

Polymarket odds for annualized April inflation of 2.3% or lower fell to as low as ~30% in early-May. This week’s release of the April headline CPI print — the lowest annual increase since February 2021 — came in below 2.3%, catching markets off-guard:

In response to the below-consensus April CPI print, Polymarket odds for above-3% inflation in 2025 fell significantly to 61%, down from as high as 75% just last week:

Clearly, markets are in the midst of a re-rating lower of inflation expectations. But is it warranted?

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

→ What tariff-driven inflation?

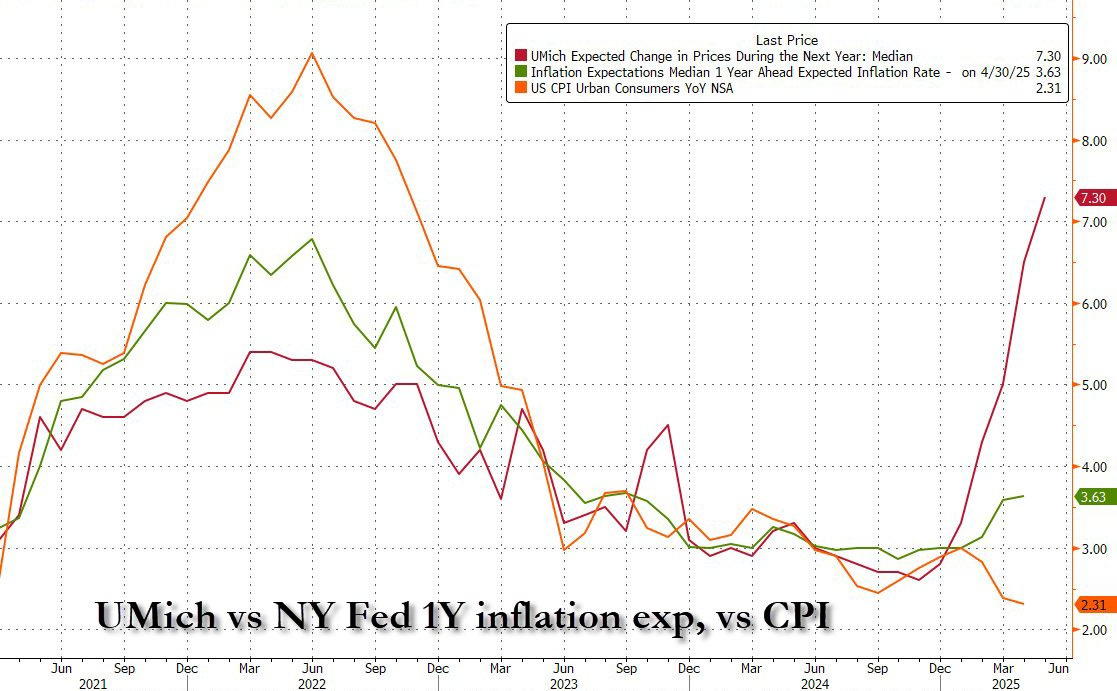

As observed among prediction market participants, following Liberation Day, inflation expectations have risen meaningfully. Higher inflation expectations have also persistently shown up in the soft data. Bar none: tariffs are inflationary, economists purport, and markets believe(d). Yet more than six weeks after Liberation Day, higher inflation — to the surprise of many — hasn’t materialized in the hard data.

This week saw a slew of important economic reports — including April Consumer Price Index (CPI) and Producer Price Index (PPI) — which were consistent with the trend of hard data defying very weak soft data:

But, as is often the case, the surface-level data here doesn’t tell the full story. Let’s start with CPI.

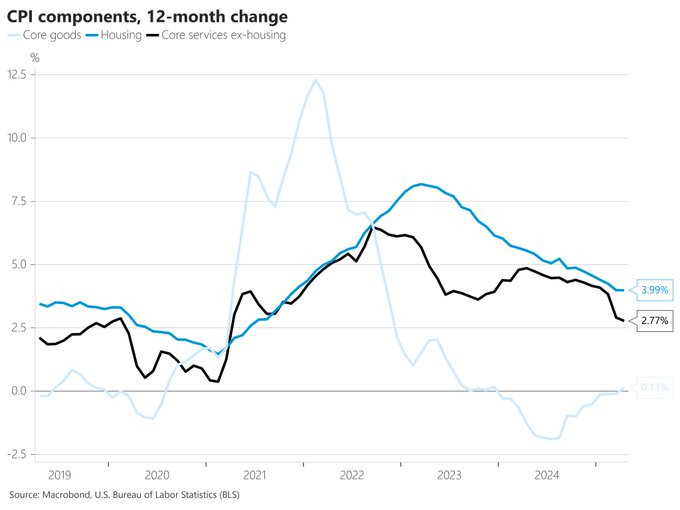

CPI rose 0.2% in April, with the annual inflation rate dropping to 2.3%. Core CPI, which excludes volatile food and energy components, also increased by 0.2% for the month, translating to a 2.8% yr/yr gain.1

Altogether, CPI has been relatively muted — both in the run-up to and following Trump’s increases in tariff rates in April. While goods deflation stalled after providing meaningful disinflationary contributions over the previous two years, housing inflation continues to stabilize as core services (ex-housing) dis-inflation accelerates:

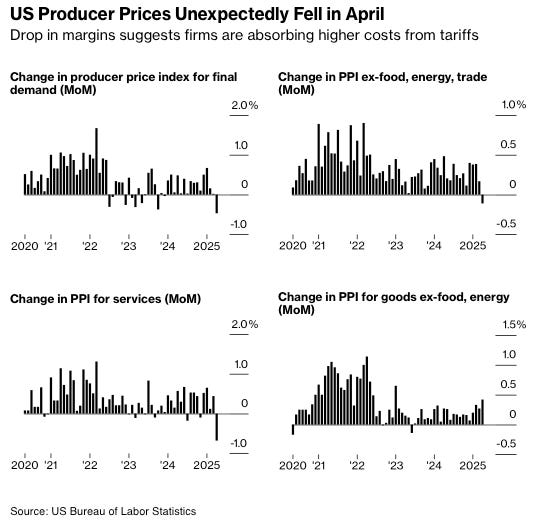

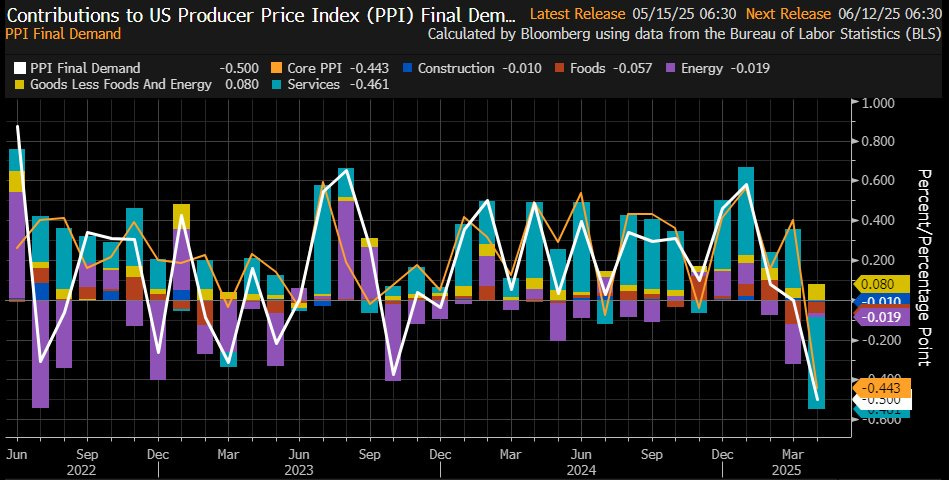

Now, PPI.

Prices paid to US producers (PPI, or wholesale prices) showed deflation in month-over-month terms (-0.5% vs. +0.2% expected) and disinflation in year-over-year terms (+2.4% vs. +2.5% expected). This was the lowest month-over-month PPI print since the April 2020 lockdowns. The story largely reflects services deflation and a slump in company margins, suggesting firms are absorbing some or all of the hit from higher tariffs.

While producers are feeling pressure from steep tariffs on imported materials and other inputs, the impact on consumer prices has remained modest. The data indicate that American manufacturers and service providers have, for now, largely held off on passing higher US import duties through to consumers.

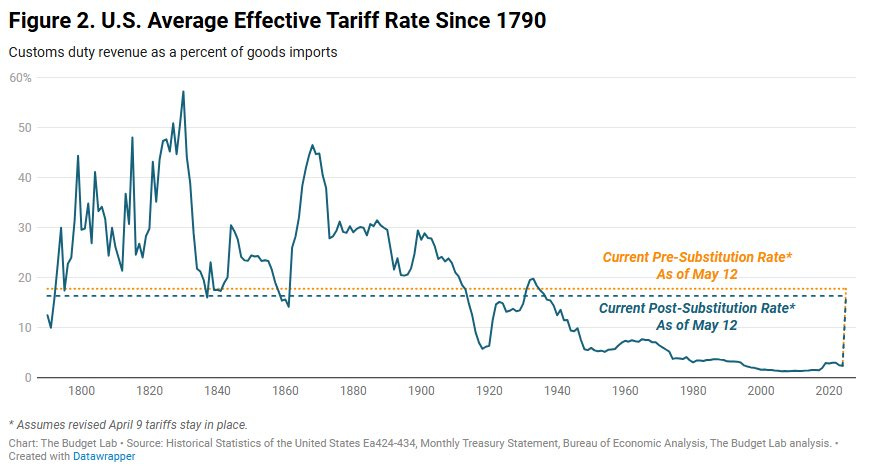

Yet still, even after the pauses of Trump’s expansive tariffs, the baseline tariff rate — 10% on most US trading partners, 30% on China, 25-50% on certain goods like autos — is incredibly high relative to history2:

So, what do we make of the surprisingly benign inflation data after a month and a half into Trump’s high-tariff regime? Some have been quick to conclude that the “tariffs are a tax; tariffs are inflationary” claims are misnomer. But among subject matter experts, namely economists, the open question has been if — and if so, to what degree — companies will pass on higher import costs to consumers.

The reality is it could very well be the case that this passing on to consumers of tariff-driven price increases on US imports is taking longer than analysts and economists had initially anticipated — that is, it’s not a question of whether it will happen, but when.

Per Bloomberg:

“For now, distributors are not passing on all these extra costs to consumers,” Samuel Tombs, chief US economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, wrote in a note. He added that it took three months after tariffs were imposed on washing machines in 2018 before consumers began seeing higher prices. “It will take more time to assess whether a sustained squeeze on margins is occurring.”

For companies that are hiking prices, the risk is the action may result in lost sales. However, not doing so poses a risk to profit margins. Most businesses, it seems, have opted to absorb a portion of the added costs to avoid dampening demand amid growing consumer unease — consumer sentiment has weakened, and retail sales, released Thursday, missed estimates, posting only a marginal increase.

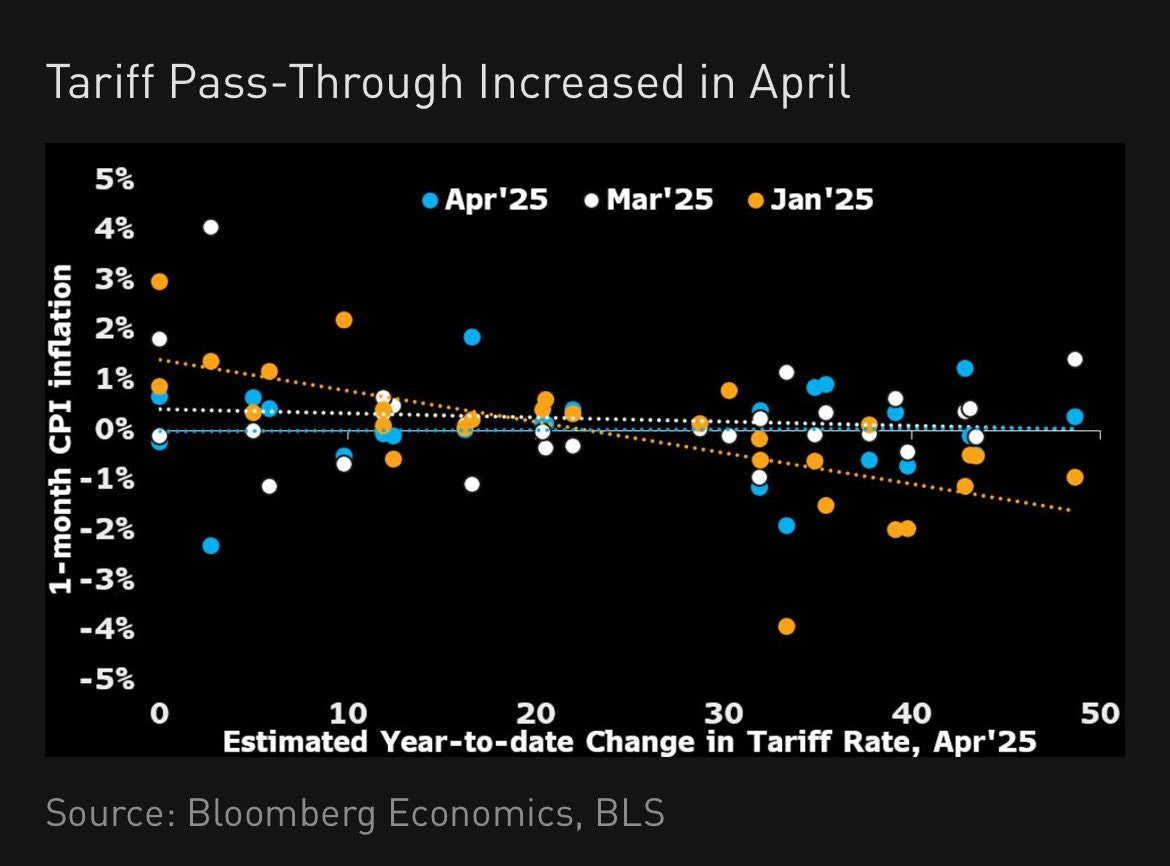

Even so, we are actually seeing some emerging signs of tariff (cost) pass-through increasing:

To thread it all together, the April CPI/PPI releases broadly reinforce the story that: 1) there is some increased pass-through of tariffs in goods prices; 2) deflation in services is offsetting those tariffs increase; and 3) the net impact is disinflation.

But logically, this can’t be sustained. Unless services deflation — driven almost exclusively by transient factors like falling portfolio management fees (due depressed stock market prices throughout April) and lower airline prices (foreign travel to the US has dried up) — persists, higher import prices will fail to be offset.

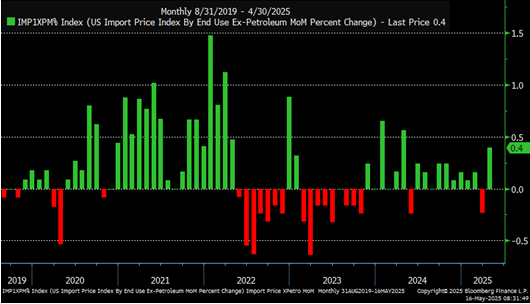

Indeed, if import prices are an indication, the result will be higher inflation once the transient services deflation subsides.

It would be foolish to expect companies to continue eating margin. For its part, Walmart — a bellwether for the retail landscape — said it plans to raise prices this month and early this summer, as tariff-affected merchandise hits store shelves. “The magnitude and speed at which these prices are coming to us is somewhat unprecedented in history,” said CFO John David Rainey.3

Even with the temporary agreement reached by China and the US to reduce additional tariffs on Chinese imports to 30% from 145%, Walmart executives warned Thursday that their operations could face significant disruption if tariffs return to prior levels. But even at the reduced rate, they said, a 30% tariff would lead to meaningful price increases for most consumers:

"We're wired for everyday low prices, but the magnitude of these increases is more than any retailer can absorb. It's more than any supplier can absorb. And so I'm concerned that the consumer is going to start seeing higher prices. You'll begin to see that, likely towards the tail end of this month, and then certainly much more in June."

Walmart — who sources about 70% of their goods from China — is the paragon of modern inventory management and and supply chain optimization. In theory, as the bona fide low-cost leader, Walmart should be the most unrushed among its peers to raise prices in sustaining profit margins. So if they’re saying with a high degree of certainty that their prices will be moving higher, and soon, then it’s safe to assume the same is true for every other retailer — online or brick-and-mortar, big or (especially) small.

Like when Jamie Dimon or Warren Buffett opine on the economic environment and markets keenly take note, so too should we take serious Walmart’s guidance on the pricing landscape for consumer goods. This isn’t, in my view, a case of a company setting itself up to under-promise and over-deliver; it’s a case of a management team with its finger on the pulse tempering expectations based on what they’re seeing.

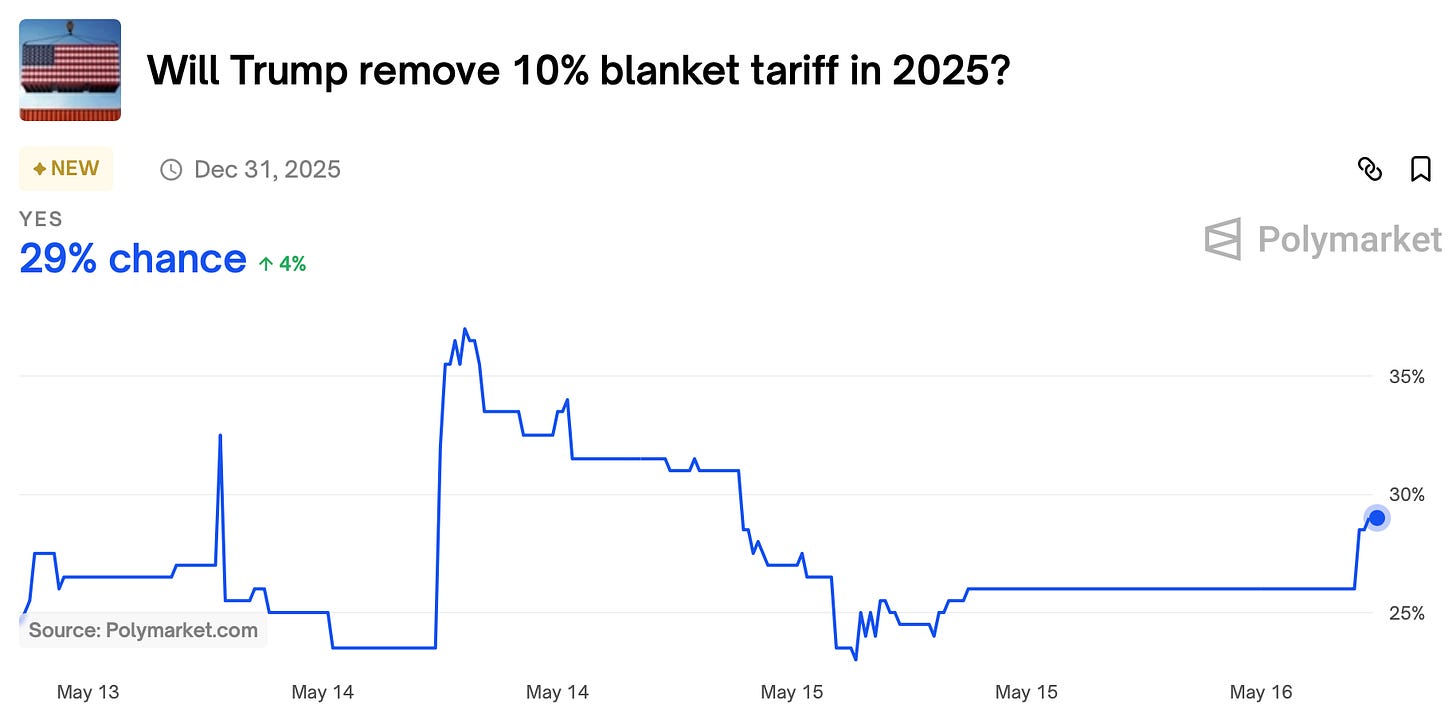

Therefore Walmart’s warning should be heeded, and we should expect inflation to return unless… unless tariffs are lowered to pre-Liberation Day levels. This, according to Polymarket bettors, is unlikely to happen (although this market should be a volatile one as Trump’s trade policy seems to shift by the day or even by the hour):

Essentially, the higher these odds go, the lower inflation expectations should go — because if the current tariff regime remains unchanged, you can take Walmart’s word that prices are going higher.

Analysts had expected tariffs would add maybe 6-7 basis points to core inflation readings in April, with the bulk of the tariff pass-through effects to come later in Q2 or in Q3. Core goods prices were +0.06% in April, vs. -0.09% in March. On the year, core goods inflation flipped from -0.10% in March to +0.13% in April:

Per Ernie Tedeschi of the Yale Budget Lab on X:

Economists should be humble & open-minded about how & when tariffs might show up in the data. At the same time it's worth emphasizing that tariffs in April were only a fraction of full strength: the average US tariff rate was 4.4%, versus a 17.8% "full strength" rate as of May 12.

Walmart and other major retailers are expected to take a strategic approach to price adjustments, selectively raising prices on certain goods while keeping core items competitive to preserve market share and margins. In some cases, non-tariffed products may see price hikes, while prices on tariffed items remain stable.

Another lens to look at this is, are tariffs more recessionary (I.E. they reduce aggregate demand) than they are inflationary?

If certain trade policies materialize as effective embargoes (for example U.S. China trade a few weeks ago) then economic activity may be halting altogether in certain sectors. I imagine this materializes differently in the CPI/PPI than more modest tariffs.

As a fun little data point from my family, I noticed that our family credit card expenditures were 1/3 below normal in April compared to the prior few month averages. Maybe we were feeling poorer given the state of our portfolio? I know that Visa and Mastercard didn’t detect that same effect societywide, but I certainly saw some corporate belt-tightening at our portfolio companies.

Sorry it’s long, but hoping you give a read and reply with what you think at some point, lol.

As you allude to, CPI and what we broadly call “prices”, “inflation” etc encompasses a massive basket. Within that, tariffs affect imports & goods/services that use imports as inputs.

Tariffs are complicated because of how passing the costs through can result in substitution.

Someone referenced recessionary effects which is part of that equation. So doubting that the end result is higher prices shouldn’t be conflated with saying that tariffs aren’t deleterious, though I definitely see people who support tariffs using arguments that basically describe bad outcomes to win the narrow battle on price effects without conceding the blow in the greater war on the wisdom of tariffs.

I think that treatment of tariffs as a concept has been way too alarmist, compared to how ESG policies were treated, which have been catastrophic on energy (prices and security) and other aspects of the supply chain in ways that aren’t just increasing price levels but truly inflationary, while simultaneously kneecapping productivity, competitiveness, and overall growth.

Trump’s specific form of tariff policy is the worst possible execution. Its maximally disruptive, maximizes the pain while minimizes any gains (as opposed to announcing tariffs a year out which would have the opposite effect), and also puts all the focus there for his department heads who could have been deregulating in the meantime to offset the tariffs, then pivoting to negotiations to ensure they’re not enacted anyway. Yes, it did give credibility to the threats and did help with playing chicken with China, but even there, the rates being so high offset those gains by being facially unsustainable.

I guess overall my point is that talk of how bad tariffs are was overblown by people like Larry Summers who accepted (with much less opprobrium) far more deleterious policies like in the pursuit of net zero and other environmental goals—which actually created famines in some instances, I believe in Sri Lanka, and raised costs on the essential good of *food*—and were indeed inflationary in the purest sense across the board.

If Trump had executed the sequencing properly, things would be way better, but lower US gas prices are still forecasted for 2025 and 2026 and that will have a huge up front affect for consumers filling the tank and on the back end when lower fuel inputs offset some of the rises, as just one example of the ways I think this might net out to the lower, in addition to negotiations. All of this happens against backdrop of AI integration, which won’t be rapid but will pick up steam as capabilities leap frog forward such that they’re undeniable and the tasks that could be replaced in, say, November of 2024 gets rapid uptake in the coming months as the advanced capabilities make the trivial a no-brainer to remain competitive.